Difference between revisions of "Paragon Times/20050413"

(new) |

m (Robot: Cosmetic changes) |

||

| (One intermediate revision by one other user not shown) | |||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

|byline3=Vol. 174 No. 413 | |byline3=Vol. 174 No. 413 | ||

|header2=ParagonTimes seifert title.gif | |header2=ParagonTimes seifert title.gif | ||

| − | |header3=[[ | + | |header3=[[File:Seifert main.jpg]] |

|headline=The Re-shaping of Paragon City | |headline=The Re-shaping of Paragon City | ||

| − | |writer=By Jackson Turner<br>Senior Times Staff | + | |writer=By Jackson Turner<br />Senior Times Staff |

|leftcol='''PARAGON CITY, April 13''' — Two events occurred in 1931 that would change Paragon City forever. In that fateful year, two very dissimilar men would arrive at the Birthplace of Tomorrow. One, a long absent prodigal son, would return heralding the rise of the super-powered hero. The other, a foreign-born artist, would change the very shape of the city itself. Both would be instrumental in the creation of a city of heroes. | |leftcol='''PARAGON CITY, April 13''' — Two events occurred in 1931 that would change Paragon City forever. In that fateful year, two very dissimilar men would arrive at the Birthplace of Tomorrow. One, a long absent prodigal son, would return heralding the rise of the super-powered hero. The other, a foreign-born artist, would change the very shape of the city itself. Both would be instrumental in the creation of a city of heroes. | ||

Rudolph Augustus Seifert, then thirty-three, had no intention of going to Paragon City that cold February day in 1931. He was in fact on his way from Cambridge to New York when a stalled train on the line ahead forced his Yankee Clipper to detour south into Rhode Island. | Rudolph Augustus Seifert, then thirty-three, had no intention of going to Paragon City that cold February day in 1931. He was in fact on his way from Cambridge to New York when a stalled train on the line ahead forced his Yankee Clipper to detour south into Rhode Island. | ||

| − | [[ | + | [[File:ParagonTimes seifert portrait.jpg|right]]The Swiss-born artist and architect, who had studied with such divergent mentors as Walter Gropius and Raymond Mathewson Hood, was on his way to New York City to meet with William Van Alen, whose art-deco inspired Chrysler Building had been just completed |

|rightcol=to great acclaim the previous year. “Mr Alen and I had been corresponding for the past several months,” Seifert wrote in his unpublished memoirs, “but only now, with my most recent work finished in Boston and Cambridge, had I the opportunity to meet the brilliant man in person. We had hopes of collaborating on something.” | |rightcol=to great acclaim the previous year. “Mr Alen and I had been corresponding for the past several months,” Seifert wrote in his unpublished memoirs, “but only now, with my most recent work finished in Boston and Cambridge, had I the opportunity to meet the brilliant man in person. We had hopes of collaborating on something.” | ||

| Line 43: | Line 43: | ||

Other triumphs soon followed: the Bradbury Tower, the Campbell Building, the Gernsback, and others. In 1939 | Other triumphs soon followed: the Bradbury Tower, the Campbell Building, the Gernsback, and others. In 1939 | ||

| − | |rightcol=[[ | + | |rightcol=[[File:ParagonTimes seifert building.jpg]] |

he created and chaired the Paragon City Architectural Commission, which coordinated and oversaw the city’s architectural revitalization. “Despite the Depression that mired the hopes and dreams of a nation, it was an exciting and challenging time,” Seifert wrote. “A new power had surfaced within the city—Statesman was stemming the tide of lawlessness and others like him were joining forces. It was like the gods of old had descended upon the city. I wanted Paragon City to reflect that feeling. I wanted to create a true city of and for heroes.” | he created and chaired the Paragon City Architectural Commission, which coordinated and oversaw the city’s architectural revitalization. “Despite the Depression that mired the hopes and dreams of a nation, it was an exciting and challenging time,” Seifert wrote. “A new power had surfaced within the city—Statesman was stemming the tide of lawlessness and others like him were joining forces. It was like the gods of old had descended upon the city. I wanted Paragon City to reflect that feeling. I wanted to create a true city of and for heroes.” | ||

| Line 55: | Line 55: | ||

Rudolph Augustus Seifert, adopted son of Paragon City, visionary and artist, died in 1981. He was 83. He never married.}} | Rudolph Augustus Seifert, adopted son of Paragon City, visionary and artist, died in 1981. He was 83. He never married.}} | ||

{{Paragon Times Archive Note}} | {{Paragon Times Archive Note}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category:Paragon Times Missing Images]] | ||

Latest revision as of 02:52, 10 June 2009

The Re-shaping of Paragon City

By Jackson Turner

Senior Times Staff

PARAGON CITY, April 13 — Two events occurred in 1931 that would change Paragon City forever. In that fateful year, two very dissimilar men would arrive at the Birthplace of Tomorrow. One, a long absent prodigal son, would return heralding the rise of the super-powered hero. The other, a foreign-born artist, would change the very shape of the city itself. Both would be instrumental in the creation of a city of heroes.

Rudolph Augustus Seifert, then thirty-three, had no intention of going to Paragon City that cold February day in 1931. He was in fact on his way from Cambridge to New York when a stalled train on the line ahead forced his Yankee Clipper to detour south into Rhode Island.

The Swiss-born artist and architect, who had studied with such divergent mentors as Walter Gropius and Raymond Mathewson Hood, was on his way to New York City to meet with William Van Alen, whose art-deco inspired Chrysler Building had been just completedto great acclaim the previous year. “Mr Alen and I had been corresponding for the past several months,” Seifert wrote in his unpublished memoirs, “but only now, with my most recent work finished in Boston and Cambridge, had I the opportunity to meet the brilliant man in person. We had hopes of collaborating on something.”

That “something” was never meant to be. As Seifert’s train approached Central Station near City Park (now Atlas Park), his eyes caught sight of “this rough-hewn jewel, set between a winter sea and the pastoral hills of southern New England. I could feel the lightning-tinged dynamics of change in the air—the very yearning for a future both grand and heroic. Until that vision, Paragon City had remained to me but a common industrial seaport in search of an identity, known more for its corruption than its contribution to cultural beauty.”

In that year, with the full dark weight of the Depression beginning to make its presence felt, Paragon City was a city in rapid, some said reckless, transition. Industry and commercialism, the lifeblood of any seaport town, had brought quick wealth and dubious respectability to many in both the private and public sectors. But by 1931, the tide of largess and opportunity had receded. Crime, organized or otherwise, was reaching epidemic levels. It was a city of bootleggers. Of criminal and political bosses who ran ruthless machines. In the years preceding the Depression, architectural monuments to commemorate and solidify this orgy of greed and power had sprung up throughout the city’s zones in haphazard fashion.

SEIFERT

continued from page 1E

“There was no higher purpose other than vanity,” Seifert wrote. “The bigger and gaudier the building, it seemed, the more important the man who commissioned the work.” On that winter’s day, as Seifert unwittingly rode towards his destiny, Paragon City, despite its still potent commercial might and affluence, was on the verge of becoming the artistic and architectural blight of the northeastern seaboard.

That day, Rudolph Seifert understood instantly that his destiny resided not in New York, but here in the raw, unfulfilled potential of Paragon City. He also divined that he would devote the rest of his life to the re-shaping of his newly adopted city. He would later write, “Marcus Cole (Statesman) and the others would be responsible for the physical health and security of the city. My charge was the aesthetic, the artistic--the memory of heroes past and the hope of heroes future--embraced in concrete, steel, brick and mortar.”

In that moment, the dawn of heroes was already breaking over the city. Paragon City’s prodigal son had returned with a mission. Like Seifert, Marcus Cole saw the potential of Paragon City. As Statesman, Cole would begin the city’s transformation from the back alleys and cobbled streets. Seifert would begin with a single building.

It was to Ashburn and Cross that Seifert approached with his vision of a new Paragon City. Considered the best architectural firm in the city, Ashburn and Cross had for the past thirty years designed the majority of Paragon City’s grandest structures. Often at odds with the bosses that ran the city, and caught between the necessity of being employed and maintaining some measure of respectability within architectural circles, they nevertheless managed to avoid the stigma of lesser firms and even contribute to what beauty the city still retained.

“Rudolph Seifert was not an imposing figure, slight of build, and limping from a childhood bout with polio, nevertheless he came on like a man possessed with a holy vision,” wrote Alexander Cross, then sole owner of Ashburn and Cross (William Ashburn had died in 1929). “I was familiar with his work in Boston, of course, and gladly offered to hear him out.”

Though Seifert had grand plans for the city swirling in his head, he was clever enough to suggest a single project—one that he was originally bringing to William Van Alen. “At the time, we were in the initial stages of a new design,” Cross wrote, “A grand hotel just off City Park along Paragon Circle. Seifert’s design was a thing of beauty—much more elegant and grand than we had envisioned. We knew that once the party who had commissioned the hotel saw these plans, they’d want nothing else.”

And so was born a partnership that would set the tone for Paragon City’s revival over the course of the next forty years. In 1933 Seifert, now a full partner with Cross, saw the completion of his now legendary Hotel Geneva (the original building in Atlas Park). A towering symbol of elegant form and function, the Hotel Geneva would, before its partial destruction during the Rikti War and later reconstruction, boast the company of kings, presidents, super-powered heroes and renowned artists from around the world.

Other triumphs soon followed: the Bradbury Tower, the Campbell Building, the Gernsback, and others. In 1939

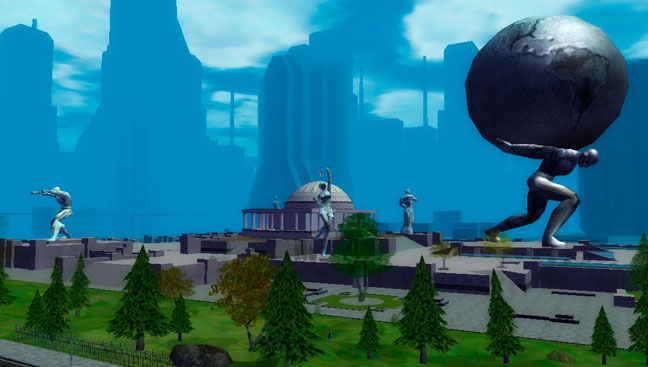

File:ParagonTimes seifert building.jpg

he created and chaired the Paragon City Architectural Commission, which coordinated and oversaw the city’s architectural revitalization. “Despite the Depression that mired the hopes and dreams of a nation, it was an exciting and challenging time,” Seifert wrote. “A new power had surfaced within the city—Statesman was stemming the tide of lawlessness and others like him were joining forces. It was like the gods of old had descended upon the city. I wanted Paragon City to reflect that feeling. I wanted to create a true city of and for heroes.”

Despite Seifert’s many accomplishments in creating a city worthy of the principles of the heroes he admired, the crowning achievement of his life would rise out of the ashes of war, from the blood and honor of patriots. On that dark and infamous December day in 1941, when so many heroes unselfishly met the threat of invasion without hesitation, when so many, in the tumultuous years to come, never returned home, Seifert vowed to remember their sacrifices. “From them, the fallen, I was entrusted with the sacred duty of remembrance. From what skills I had, from what tools were at my disposal, I sought to create a lasting memorial in the form I thought befitting their almost mythic, legendary stature—the Greek Revival. They had sacrificed so much to keep our city, our nation, and our world free from tyranny, and I wanted it to stand for all to see and be inspired by. It would be their memory forever enshrined.”

In April 1946, as the long New England winter began to recede and the trees along the new greenway parks bordering the city’s center began to bud, Seifert stood with Statesman and the surviving members of his corps of heroes, and bowed their heads in silent reflection. Statesman then straightened and saluted the newly completed statute of Atlas. All around him, the graceful, titanic statues of the fallen seemed to rise up to touch the brightening sky. “For the past, the present and the future,” he said to the thousands gathered. “I dedicate this memorial as Atlas Park. All who visit this site will take inspiration from the heroic deeds of these champions. We are in their debt. We will never forget their sacrifices.”

Though Seifert’s long career would see the completion of many award-winning buildings and structures, the two that would remain most important in his eyes were Atlas Park and Valor Bridge in Independence Port. “I owed the heroes of Paragon City my heart, my dreams, my very reason for being… it was the only true way I had of saying thank you.”

Rudolph Augustus Seifert, adopted son of Paragon City, visionary and artist, died in 1981. He was 83. He never married.